Canapés, wine and jazz legends in the living room

In 1990 Polydor Germany was looking for a jazz product manager. Six months after the position had been advertised, nobody had yet applied for it. Tim Renner, then Polydor’s Progressive Music department manager and Götz Kiso, Polydor’s managing director, decided to talk me into taking the job. My task, to modernize the jazz brands Verve and ECM.

As a jazz product manager, I was musically an outsider at Polygram from day one. The job promised no single or album hits, no artists in the big Saturday night TV shows like Wetten, dass…? and no gold or platinum award albums. Instead of the glamourous life of show-biz I spent my time in dry discussions about long jazz solos with jazz nerds and know-it-all journalists or angry jazz fans who had left their wives at home, if they had ones at all. For hours on end I had to convince sales department employees and ignorant record dealers to pay attention – at least for a moment – to new jazz releases. Ok, I get it, sometimes their hesitation was understandable. In a WOM or Tower Records store many jazz releases only sold in 20 years what a summer hit did in five minutes. And that was only the best-sellers. No wonder Polygram’s focus was on hits. Quantity! Phonogram boss Louis Spillmann summed up the company’s philosophy: Down with quality – up with the charts!

My boss Tim Renner was an expert in punk, new wave, pop and electronic music. Maximum song length: 3 minutes. And no solos. He couldn’t stand a jazz track longer than 30 seconds, but he was itching to succeed in marketing jazz so that he wouldn’t stand as a traitor among his friends. Jazz was anything but hip in those times of disco, punk, new wave and techno. Besides, Renner also wanted to score with the Polygram world boss, the Frenchman Alain Levy. Jazz had experienced an unexpected boom in France at the end of the 80s. “That must work in Germany, too”, Levy insisted to Wolf-Dieter Gramatke, the German boss at that time. As a good german Gramatke replied, “Of course, Sir!” He handed it over to Renner who it handed over to Kellersmann. “Take over!” “Yes, Sir!”

Day one I started to discover what the word ‘acquisition’ meant. The Polygram Group had spent decades taking over one indie jazz label after another.

Thanks to my homemade mix tapes, the labels I know were few and far between, mostly stickers on cassettes with labels like TDK SA90 and Maxwell XL II 90. The credits on the covers were reduced to artist and title names. Now I came upon many of these artists released on such Polygram labels as Mercury, A&M, EmArcy, Horizon, Philips, King Records, Amadeo, Sonett, Barclay, Fontana, East Wind, MGM, Delite Records, Motown, Chess, Elenco, Brunswick, Decca, JMT, Polydor, Verve and MPS. What a treasure fell into my hands!

In addition to all these international labels, almost every national company had released local jazz artists over the decades. This happened out of a sense of duty – “We are not only doing trash – we take care for our local culture.” And it helped cultivate local friendships. The bridge-playing friend of the CEO’s wife has a brother who is a jazz pianist… Or jazz was in one of its momentary upsurges, as in the early 70s. Sometimes it was just positive subversion. Like when an A&R- manager had a secret passion for jazz and found a way to support it alongside his mainstream pop business.

For these reasons and more, Polygram had developed a huge reservoir of many of the world’s greatest jazz labels and artists. Since it seemed commercially uninteresting, however, the archive wasn’t really being taken care of. Only a very few dusty old employees could give specific information. Most of them had been transferred to the some corner of the administration department and were already counting the days until retirement.

MPS was one of the labels I came upon in 1990. It was bought in 1983 by Rudi Gassner, a boss at Polygram at that time, who had a soft spot for jazz. However, Gassner left Polygram shortly after the MPS acquisition and the label’s tapes became dust catchers along with the other jazz labels in the archive.

Of course this annoyed MPS founder Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer. His friends called him HGBS. Over the course of more than 20 years, HGBS had initiated, financed and published more than 500 releases for MPS, many of them truly influential. Shortly after the sale he feared that his life’s work could be forgotten.

HGBS was a passionate music lover and a technology freak. Born in 1927 in Villingen in the Black Forest, he was introduced to music at an early age by his father Fritz Brunner, an accomplished violinist, pianist and conductor. After marrying into the Schwer-family, a family of industrialists in Villingen, HGBS’ father switched to work in the electronics industry. HGBS’ grandfather was the founder of the company SABA (Schwarzwälder Apparate Bau Anstalt – Black Forest’s Institute for Mechanical Engineering), which later became known worldwide for the production of TV and radio sets. After the war, HGBS joined the company, first working for the Internationale Film Union, a laboratory and dubbing company, and then for Siemens. In 1957 he joined SABA, where he became technical director in 1960. His brother Hermann headed the commercial department.

HGBS first heard jazz during the war. He discovered it by chance when Glenn Miller played on the English and American radio stations people were listening to clandestinely. The penalty for being caught listening to “enemy stations” could be death. HGBS also loved German dance and easy-listening music, which was recorded on behalf of the German Ministry of Propaganda, even though this music was musically and rhythmically sanitized. His other musical passions were pop, classical and folk music. A true musical all-rounder. His credo: “The musical statement must be real.”

His music-production activity began in the 50s with, among others, Horst Jankowski, Hans Koller and Albert Mangelsdorff. In 1963 he started hosting house concerts in the living room of his private villa in Villingen. The concept was simple. He invited an artist, often an international star, to appear solo or with a band. Listening would be a small, select circle of friends, musicians, business partners and journalists. While the guests were treated with canapés, wine and live music, HGBS went to the control room, where he supervised the live recording from his mixing desk.

His taste was impeccable. The first concert featured Oscar Peterson, who was at the peak of his career and on a world tour. After a concert in Zurich he was picked up by HGBS’ private driver who drove him directly to Villingen, where he performed at the house concert. He received his full concert fee. Given the respect and warmth of HGBS’ welcome, he and Peterson became fast friends and Peterson would start making detours to the Black Forest more often. Over the years, many other internationally acclaimed artists found their way to the Brunner-Schwer living room – Bill Evans, Duke Ellington, George Duke, Monty Alexander and Friedrich Gulda, to name a few.

In 1963 HGBS released the first productions on the new SABA label, which he founded. In 1968 the Brunner-Schwer brothers sold the SABA company for a large sum, freeing Hans Georg up to pursue his passions: collecting Maybach automobiles, deepening his knowledge of studio technology and, most importantly, producing music. He founded the MPS label (Musik Produktion Schwarzwald), which immediately became Germany’s premier jazz label. Along with HGBS, Joachim-Ernst Berendt became the label’s most important producer. While HGBS was more dedicated to mainstream jazz, Berendt concentrated on more experimental production. Another important producer was Gigi Campi, who worked in Cologne and was the mastermind of the Clarke Boland Big Band. Between 1968 and 1983, the MPS label released the broadest variety of jazz and experimental music, from the Singers Unlimited, George Shearing, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Archie Shepp to Sun Ra, Rolf Kühn, Joachim Kühn, Jean-Luc Ponty, Michael Naura and Art van Damme, with Joanne Grauer, Mark Murphy, Monty Alexander, Ernest Ranglin, and Baden Powell thrown in for good measure. That and so much more.

After HGBS sold the label to Polygram in 1983, there were only very sporadic releases until 1992, after I’d become the new MPS boss in 1990. At first I wasn’t aware of the label. My focus was on Verve, ECM and Talkin’ Loud. But there were frequent calls, faxes and letters from frustrated MPS artists asking about the availability of their albums. Once drummer Charly Antolini came unannounced to my office. Outraged he protested loudly that we were boycotting the sale of his albums. Drummers can be highly emotional people.

In the summer of 1991 I got my first letter postmarked Villingen-Schwenningen. “Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer” was printed on the letterhead, along with “Fabrikant,” an old german expression for factory owner. HGBS was visiting his son in Hamburg and wanted to use this occasion to get to know me. MPS was for me still a book with seven seals at that time, but that would soon change.

We arranged to meet on a Sunday afternoon at the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten, Hamburg’s best address. It was the hottest day of the year.

Of course I wanted to appear right on time and freshly showered in my new suit. The young Hamburg product manager meets the Black Forest Fabrikant. But that’s not what happened. The day before I played a gig with Andreas Dorau, a German pop artist, in Rostock. A local fan had fulfilled his dream to hire Dorau and the band “Der Plan” for a concert. Rostock was once part of the German Democratic Republic, the former east. Almost nobody knew the bands from West Germany just one year after the reunification, so we shouldn’t have been surprised when only 50 people showed up.

Though disillusioned after the short-term euphoria of reunification, we set out to explore the exotic city of Rostock after the gig. By early morning the night of excess culminated at the last open snack bar still open.

Slightly sobered up but still reeking from alcohol, we headed to Hamburg around noon. We had not taken into consideration the desolate roads of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, which had not been repaired since the war. No surprise, then, that the maximum speed limit was 60 km/h. After more than a one-hour delay we reached Hamburg. Sweaty and hungover, with two saxophones under my arms, I headed straight to the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten, where HGBS waited, grumbling, in the reception hall. Not a good omen for our first meeting.

We went to a nearby restaurant. German cuisine. First a Doppelkorn (double grain schnapps) and a freshly tapped beer. It was still unbelievably hot. Another Doppelkorn and another freshly tapped beer went down well. A two-hour monologue followed, only interrupted by the waiter, who handed us further refreshment. Now HGBS let off the steam that had pressurized for years. His catalogue was no longer available. All the important MPS albums had been taken from the market. His life’s work was buried in the Polygram tape archive. He regretted the sale of MPS. I could hardly reply. He was right on all points.

After two hours the atmosphere started to lighten up. The schnapps, the heat the cold beer and the pressure valve had the desired effect. Now even my hungover rock star condition was an advantage. HGBS had a soft spot for musicians and people who lived for music. The two saxophones under my arms dressed me better than any new suit could have done.

He offered his help to evaluate the catalogue. No financial expectation. But there was a condition: The remastering of the old recordings would be done under his control. The Most Perfect Sound, he called it, by HGBS.

He started where he had back when he was first recording, with Oscar Peterson. Under the original title “Exclusively For My Friends,” the house concerts came out at the end of the 60s. What began as six original LPs, now became a 4-CD set. This was back when record collectors were ridding themselves of their vinyl collections to replace them with expensive CDs. Sounded much better, of course!

The search for the original artwork turned out to be problematic. In a visit to the master tape and cover archive in Hannover-Langenhagen, we discovered to our horror that all the original photos and production films had been destroyed. None were saved digitally. One smart controller had decided that there had to be more space in the library for the new hits. Spring cleaning in the Polygram archive. So for these and all later releases, we had to laboriously obtain the artwork materials from collectors and rephotograph them.

It was worth the effort. The Peterson release exceeded all expectations. A small note in the weekly magazine Der Spiegel was enough to sell 5 thousand boxes in Germany alone within just the first few days. As bad luck would have it, it was only 3 weeks before Christmas so the delivery time for the next pressing was a full four weeks away. For the accountants among us, the box had a retail price of DM 80. The retail price was 4x High price, making it a DM 400.000 revenue in Germany alone. Not bad for a low key jazz re-release, with almost no costs to speak of. Then came international sales especially in the USA, Canada, France and Japan. Even the pop department was impressed.

From now on MPS was our priority. Brunner-Schwer had carte blanche to pick through the vaults. He could fulfill his next dream, a double CD with his favourite piano recordings from 20 years of recordings – the MPS Piano Highlights.

For these ‘highlights,’ everything had to be perfect, more elaborate, chic and exclusive. Together with the graphic designer Dirk Rudolph and the author of the liner notes Jörg Eipasch, I travelled for the first time to Villingen, in the Black Forest, to discuss the release. HGBS and his wife Marlies welcomed us like kings with a hearty dinner, non-stop kirschwasser (cherry brandy) and a full audition of MPS Piano Highlights at full volume in the very room where it was all recorded. We saw first hand the passion and hospitality that Oscar Peterson, Duke Ellington and all the other world stars had experienced before us.

HGBS was happy that we gave his MPS Piano-Highlights our full attention. The booklet was given a special colour printing, with detailed English and German liner notes all tucked into an impressive slipcase. Designer Dirk Rudolph was already known to our Chief Financial Controller, but for all the wrong reasons. His works were presented at internal training sessions as a prime example of how not to create CD packaging. He designed a Philip Boa 12” in such exclusive packaging that the printing costs exceeded even the retail price, causing a loss for every record sold. But there are times when you don’t listen to the CFO. The MPS Piano Highlights was about culture. It was about prestige. We went ahead with it. So as not fall into the “out of stock” trap again we increased the number of copies of the first edition. We wouldn’t again risk running out of the product just before Christmas.

In great anticipation and thinking of the huge success of the Oscar Peterson set, we looked upon the release with great anticipation.

Nobody wanted it.

Flops can be quickly forgotten. But 6 months after the release the Polydor chief controller burst into my office. “Mr. Kellersmann, do you know the box-set MPS Piano Highlights?”

“Yes, isn’t it a great box, Mr. Seibt?”

He took a deep breath then rustled the folder “Flat fee penalties for excessive packaging” in front of my face. These were the new controller guidelines from headquarters in Holland. According to stringent new rules from our Dutch controllers, the optimal CD consisted of a cheap plastic case stuffed with a two-page booklet. But of course every artist and product manager wanted the most beautiful release. A CD for eternity. Heritage!

The new guidelines defined the scope and the packaging for each release. Offenses were punishable with penalty points, and 8000 Dutch guilders for each “excess.” The headquarters counted eight excesses alone in MPS Piano Highlights, resulting in 64.000 guilders. The CDs were stacked unsold in the warehouse. We wanted to be able to deliver. But not only did we have a high penalty, we were racking up storage costs for high unsold inventory at the same time…

We continued to issue the catalogue but now with slightly less optimism. HGBS remastered the complete recordings of The Singers Unlimited, a 7-CD edition. Gilles Peterson compiled the series Talkin’ Jazz with DJ and MPS-expert Rainer Trüby; MPS collector Stephan Steigleder compiled CDs from groundbreaking productions by Rolf and Joachim Kühn and Wolfgang Dauner; and my colleague Matthias Künnecke provided his easy-listening friends all over the world with such beautiful CDs as “Snowflakes.”

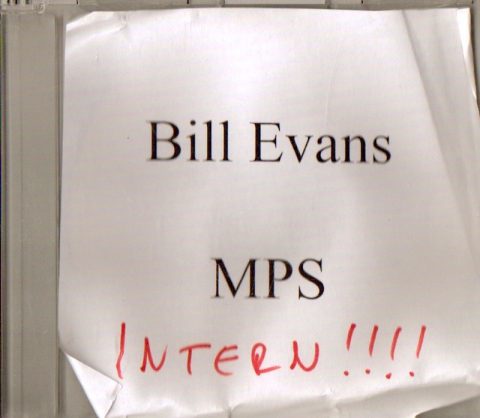

In 2004 the cooperation with HGBS suddenly came to a tragic end when he died in a car accident in Villingen at the age of 77. Music producers at that age should be particularly careful behind the wheel. In addition to HGBS, Joachim-Ernst Berendt and Monti Lüftner died the same way at the the same age. HGBS had been immersed in reviewing a rich series of unreleased house concerts. Among others there was a recording of Bill Evans. He’d given me an unmastered CD, but something held him back from readying it for release. In 2016 I was surprised with the news that this “exclusive” had been given to Resonance Records by the former heir to the MPS archive.

In 2013 Universal Music sold MPS. The reason: Universal acquired EMI and EU antitrust law stipulated that one company couldn’t unduly dominate any one market. With the EMI purchase still under consideration by Brussels, Universal offered to part with some labels and MPS was one of them. The Beatles against Oscar Peterson, Joachim & Rolf Kühn and the MPS Piano Highlights. Not a tough choice.

In a bidding process, the company Wolfgang Vaults made the best out of eight offers. They are a company that has created a successful niche for itself by commercializing concert recordings. Their holdings, and their name, came with their first acquisition, legendary concert promoter Bill Graham’s archive of music from his world-famous clubs, The Fillmores East and West. Graham was born Wolfgang Grajonca, hence the company name. Graham, who died in 1991, had recorded all concerts in his locations and was famous for the psychedelic artwork, which impressed me very much as a teenager.

I had just left Universal when the selling broker contacted me. He was grateful to have found someone familiar with the history of MPS. I gave him the contacts to the Brunner-Schwer family as well as to collectors and other experts on the label. A future collaboration appeared as a possible job perspective for me. I saw myself in sunny southern California, listening all day to Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane recordings among a coterie of old hippies while re-evaluating the MPS catalogue. Yet after all the details had been negotiated, the Wolfgang Vaults owner withdrew his offer one day before the contract was to be signed. Until today I don’t know why. The MPS catalogue went into the deep freeze at Universal Music.

A few months later the founder and owner of Edel AG, Michael Haentjes, contacted me during my sabbatical year in Rio de Janeiro. Since I hadn’t heard any news about the MPS sale for months, I suggested he ask at Universal. There they pulled the folder out of the drawer and saw that the deadline set by Brussels was close to expired. MPS had to be sold right away. Haentjes grabbed the chance and Edel AG became its new home. Shortly afterwards I started to work for Edel.

We reactivated MPS. In 2015 a new release came out after a 32 year delay, the trio Khalife-Schumacher-Tristano. Further new productions followed. Rolf Kühn, Hamilton de Holanda, Django Deluxe with the NDR Big Band, Lisa Bassenge with the Larry Klein production of Canyon Songs, the first time ever release of the last Baden Powell live recording from the year 2000, Malakoff Kowalski, Mari Boine, Malia, Barbara Dennerlein and China Moses. The response was overwhelming: Echo Jazz awards, awards from German music critics and, of course, positive feedback from passionate jazz fans around the world. In addition to the new productions, selected reissues were released on CD and LP. Among others the Oscar Peterson’s Exclusively for my Friends, a 6-LP vinyl box set (and on CD, with previously unreleased material); a 7-LP box set with the complete George Duke MPS recordings; Gilles Peterson’s wonderful double-LP compilation Magic Peterson Sunshine as well as the complete MPS catalogue made available for download and streaming.

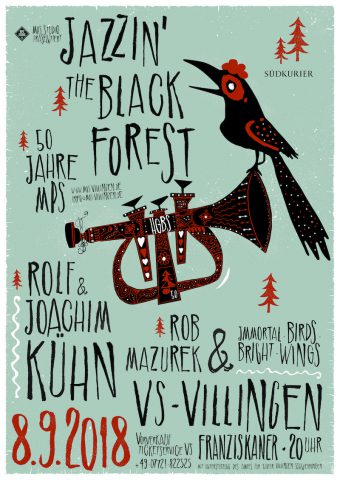

In this special anniversary year we * continue with many new releases: Rolf Kühn with Yellow + Blue, Nicola Conte with Let Your Light Shine, Malia with Ripples (Echoes of Dreams), Malakoff Kowalski with My First Piano and the young singer Erik Leuthäuser, whose album Wünschen was produced by Greg Cohen and sets a new benchmark in jazz vocals sung in German. In addition, Till Brönner, Götz Alsmann, Ed Motta and Gilles Peterson have all become MPS Ambassadors, invited to select and present their favourite album from the catalogue. Finally there will be an MPS Festival in Villingen from September 7th to 9th. Rolf and Joachim Kühn are confirmed as highliners.

Sadly, the anniversary year is complicated by conflicts between the support association MPS-Studio Villingen e.V. and HGBS’s son, Mathias Brunner-Schwer. This Black Forest thriller can be followed in the local press. But we won’t let it spoil the party. Happy Birthday MPS!

* I left MPS/Edel in December 2018 and I have started the new label “Modern Recordings at BMG Rights Management.

Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer and Oscar Peterson. (Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin the Black Forest” – Monitorpop)

Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer, Milt Buckner and Marlies Brunner-Schwer (Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin’ the Black Forest” – Monitorpop).

Joachim-Ernst Berendt and Nathan Davis. (Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin’ the Black Forest” – Monitorpop).

Oscar Peterson with “The Singers Unlimited”.(Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin the Black Forest” – Monitorpop).

Listening-Session at the MPS-Studio. With Mike Hennessey and Mathias Brunner-Schwer. (Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin the Black Forest” – Monitorpop).

MPS-Distribution-Meeting. With Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer (5. from l.), Willi Fruth (6.froml.) and other MPS-employees (Foto: aus dem Buch “Jazzin’ the Black Forest” – Monitorpop).

Listening-CD of the Bill Evans-recordings, which HGBS provided me before his death. The recording was released on Resonance Records in 2016.